Some big events are taking place in Nagano prefecture: the Iida Oneri Festival; the Onbashira Festival of Suwa Taisha Shrine; and the Hotaka Shrine Shikinen-sengu Festival. Here, however, I would like to introduce you to a special event called Gokaicho. It happens only once every seven years, at the sacred site of Zenkoji Temple. People arrive by the thousands, seeking spiritual fulfillment and peace in their lives. To this end, I can think of no better way to reach this historically important place than to walk the ancient Zenkoji Kaido road.

Book our

Tours in Nagano City

Nowadays, anyone can easily visit the temple by train or car. In the old days many people made their temple pilgrimage on foot, hoping that their efforts would help them reach the paradise of the Buddha in the after-life.

Walking the ancient road to Zenkoji, in the footsteps of countless pilgrims, one comes to know, or perhaps to feel, the history of this deeply spiritual and very special place. So come along - share the experience of the old Buddhist pilgrims as we travel this ancient road together.

So what kind of temple is Zenkoji? Why did this temple attract countless people? And how did the people in the old days make their way there? Let’s find out!

Table of Contents

・What kind of temple is Zenkoji?

・What kind of road was the Zenkoji Kaido?

・What was it like to walk the Zenkoji road?

・What is “Gokaicho”?

・The allure of the pilgrimage: the feeling that only comes when you walk the road yourself.

What kind of temple is Zenkoji?

The Main Hall of Zenkoji Temple (photo: Zenkoji Temple Office Director)

Zenko-ji, written 善光寺, translates as “Virtuous Light Temple”, with the connotation of ‘virtuous’ being not an observable trait but a quality that comes from within. Founded in the 7th Century before Buddhism in Japan diverged into several sects, Zenkoji now serves both the Tendai and Jodoshu schools of Buddhism, and is said to house the first Buddhist statue ever brought to Japan.

Zenkoji Temple’s iconic main prayer hall is a ubiquitous symbol of Nagano prefecture.

Where is Zenkoji Temple?

Access Routes to Nagano Prefecture (image: City of Matsumoto)

Zenkoji Temple is located in northern Nagano Prefecture, in the center of the City of Nagano, a straight thirty-minute walk from Nagano Station. The Hokuriku Shinkansen bullet train runs directly from Tokyo Station. Arriving by car via the Joshin-etsu Expressway the nearest exits are the Nagano and Suzaka “IC” interchanges. The nearest airport is Shinshu Matsumoto Airport, west of downtown Matsumoto.

Nagano, which means “long field”, owes its name to the characteristic terrain.

Amida Buddha: Principal deity of Zenkoji Temple

Zenkoji Nyorai (source: Zenkoji Kaido Famous Places [善光寺道名所図会, 1849], Toshitada Toyoda)

This particular image, however, is unique in that the three are backed by one halo, forming the Ikko Sanzon - “One Halo, Three Deities''. This rare depiction is often referred to as the Zenkoji Nyorai.

Shinto gods and Buddhist deities are revered as patrons and protectors of their own particular realms. What is the realm over which Amida, the main object of worship in Zenkoji Temple, presides?

It is said that Amida can deliver to the Pure Land Buddhist heaven anyone who puts their faith and trust in him.

Until the end of WWII, when simply surviving daily life was a struggle, people found spiritual strength in the belief that if they prayed to Zenkoji Nyorai with all their heart they would be reborn in the next world, their souls finding salvation in the paradise of the after-life.

Stone monument with the inscription “Namu Amida Butsu”, the mantric Nenbutsu prayer to Amida Buddha. (photo: Shigeki Tamura)

In Japan, the Buddhist prayer “Namu Amida Butsu” is well-known. The meaning of this prayer is to believe in Amida and entrust ourselves to him.

Though these prayer stones can be found throughout Japan, this one is unusually large. Imagine not only the cost but the sheer effort of obtaining such a huge stone, then carving the inscription and placing it here as a source of inspiration for all passersby to believe. Considering that it was made possible through donations from ordinary people leading modest lives, we can imagine how devout people were in their faith.

A sanctuary for all people and all religions

Entryway to Mt. Sanjo-gatake in Omine Mountains of Nara Prefecture, with a pronouncement prohibiting women. (photo: Kazuhisa Ogane)

The most distinctive feature of Zenkoji Temple is that it was open to both women and the general public when other temples were not.

Contrary to modern times, from the Muromachi period (1336~) to the Edo period (~1868) women were forbidden from entering some temples and sacred mountains. All over Japan there are legends about women who tried to enter these places being turned to stone.

Even in such an era, Zenkoji was open as a temple where women were able to pray for entry into heaven after death.

Statue of Nyoze Hime offering flowers of appreciation to Zenkoji Nyorai - Nagano Station (photo: Shigeki Tamura)

Nyoze Hime is known as the daughter of a wealthy man in ancient India. When she became gravely ill her father began praying to Amida Buddha in earnest for her recovery, repeating the Nenbutsu prayer “Namu Amida Butsu”. Through his sincere belief and dedication Zenkoji Nyorai intervened and returned Nyoze Hime to health.

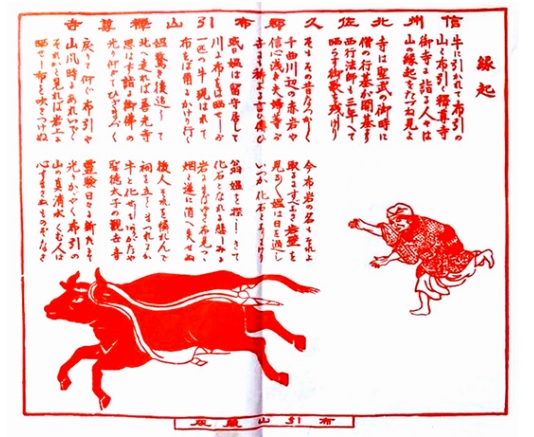

Written account of the origin of Nunobiki Shakusonji Temple, Komoro, Nagano Prefecture (photo: Shigeki Tamura)

According to the legend Ushi ni hikarete Zenkoji-mairi, a greedy, ungodly old woman was washing her clothes in a river when a cow appeared, took up the woman’s wash with its horns and ran off. The woman ran after the cow, chasing it all the way to Zenkoji Temple where she lost sight of the beastly thief. Exhausted and faced with nightfall, the woman had no choice but to sleep in the main hall of Zenkoji. During the night she was visited by Zenkoji Nyorai, an event that compelled the woman to change her ways and become one worthy of heaven in the afterlife. Upon her return home she saw that the statue of Kannon Bosatsu in nearby Nunohiki Shakusonji Temple had a white cloth hanging from her shoulder, a sign that Kannon had transformed herself into a cow in order to save the woman’s soul.

It could also be said that in an era of strict class distinction and gender discrimination, The "Good Light" of Zenkoji was one that shone on everyone in society.

Left: Stone inscribed with a poem about Zenkoji Temple, written by Matsuo Basho, the famed Japanese poet.

In his travelogue “Sarashina Kikou” Basho wrote a poem about Zenkoji, his words interpreted as praise for the temple as a special, sacred place for adherents of all sects of Buddhism.

The secret hidden in the name Zenkoji

The name of a temple often reflects the history or origin of the temple. What about Zenkoji Temple?

Actually, “Zenko” derives from the name of Yoshimitsu Honda, an official in the Asuka era (592-710) who built a temple to enshrine the triad of deities now known as Zenkoji Nyorai. As Chinese characters often have multiple pronunciations, Honda’s first name, Yoshimitsu, written 善光, could also be pronounced “Zenko”. Thus he essentially named Zenkoji Temple after himself.

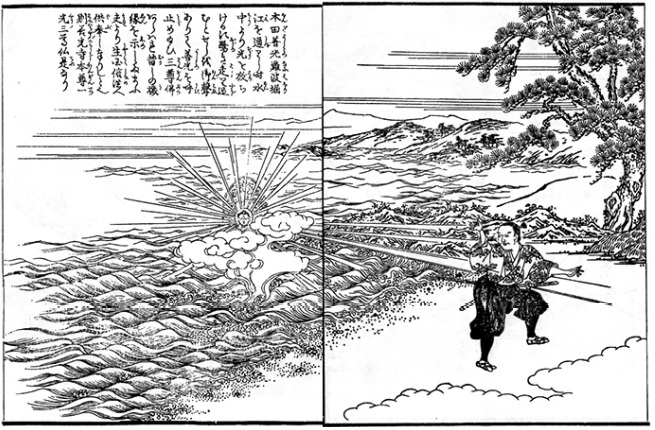

Depiction of Yoshimitsu Honda witnessing Nyorai rising from a canal in Osaka. (source: “Zenkoji Kaido Meisho-zue” picture book of famous places along the road to Zenkoji - Toshitada Toyota)

Approximately 1,400 years ago, importing Buddhism from the Korean Peninsula to Japan was a highly controversial issue. According to a certain story from the time, when a plague broke out it was believed that the original Japanese gods were punishing the people for worshiping a foreign god. To remedy the situation Nyorai was thrown into the Naniwa Horie canal. Yoshimitsu Honda is said to have pulled the statue from the water and carried it to the place where Zenkoji stands today.

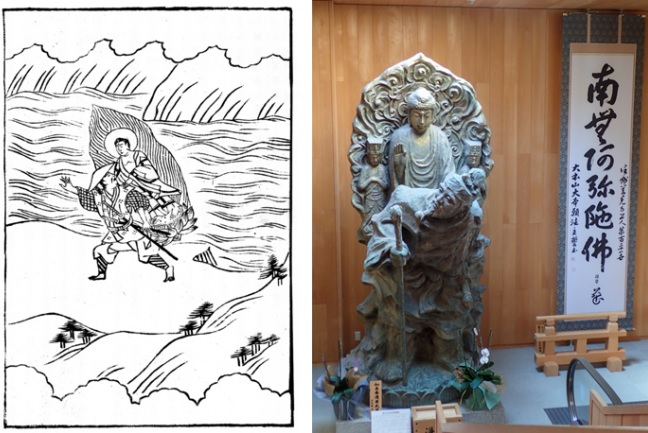

Two depictions of Yoshimitsu Honda carrying Zenkoji Nyorai. Left: “Zenkoji Engi” by Naoyori Sakauchi Right: Statue in Zenkoji Temple (photo: Shigeki Tamura)

In a separate account, Yoshimitsu Honda was on his way to the capital with a local official when Nyorai, emanating a brilliant light, emerged from the Horie canal and jumped on Honda’s back, urging him to return him to his hometown of Omi in Nagano Prefecture where he could be worshiped once more. Honda agreed, taking the first steps toward the establishment of Zenkoji Temple.

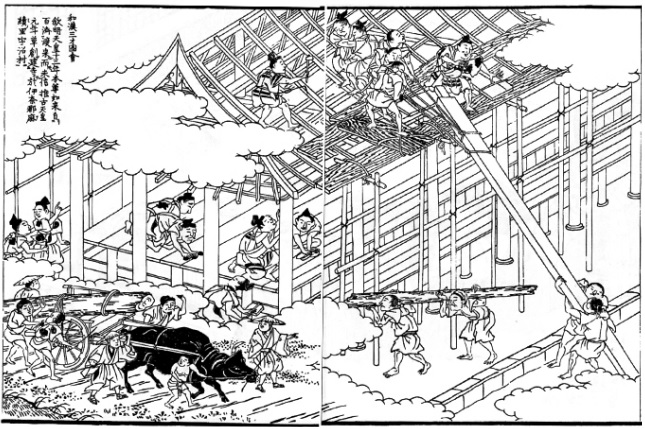

Depiction of the making of Zenkoji Temple (photo: “Zenkoji Road Famous Places” by Toshitada Toyota)

After his return to Omi, Nyorai would eventually ask Honda to take him to a place called Imoi Village, further north, where Zenkoji Temple now stands.

Zenkoji Nyorai was first enshrined in Omi, at a temple called “Moto-Zenkoji”, with ”moto” (元) meaning origin or former.

It is said that Nyorai promised to return to Moto-Zenkoji for a half a month to save people’s souls. A poem about Moto-Zenkoji Temple relates how Zenkoji Nyorai kept his vow.

For this reason, there is an expression, “kata-mairi” (one-sided prayer), to describe people who visit Zenkoji Temple but not Moto-Zenkoji.

What kind of road is the Zenkoji Kaido? What was it like to walk this road?

The Zenkoji Kaido and the major roads of the surrounding vicinity (original image: Zenkoji Kaido Council; photo courtesy of Alpine Tour Service Co., Ltd)

As the name implies (in Japanese, "kaido" means "road"), the Zenkoji Kaido was the road walked by those making the pilgrimage to Zenkoji Temple.

In a broad sense, all roads leading to Zenkoji Temple can be called the “Zenkoji Kaido.” However, when we say “Zenkoji Kaido” we refer to two specific routes: the Hokkoku Waki Oukan and the Hokkoku Kaido.

The first section of the Hokkoku Waki Okan runs from the Nakasendo post town of Seba-juku (Shiojiri, Nagano prefecture) up to Shinonoi Oiwake-juku in the City of Nagano. There it meets the Hokkoku Kaido for the second leg of the journey to Zenkoji Temple.

The suffix “juku” refers to the “shukuba” post towns that sat along the various kaido running through Japan. The main roads of these shukuba were lined with shops and inns, not unlike the main streets of today.

Walking with a purpose, 40 kilometers a day.

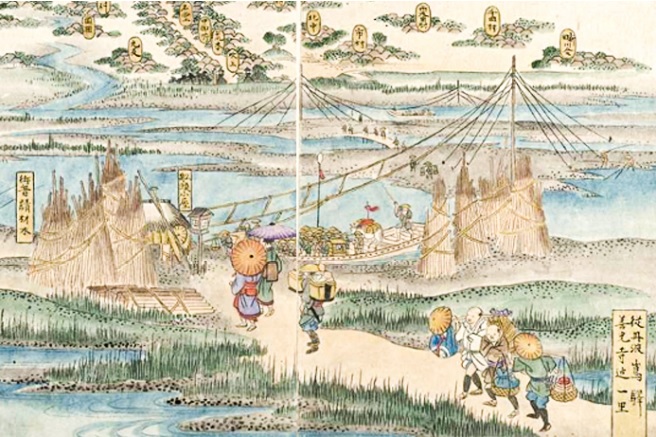

Traveling the Zenkoji Kaido in the Edo Era; passing through Tanbajima-juku, not far from Zenkoji Temple. (photo courtesy of the Shinshu Regional Historical Materials Archive)

From the earliest days, Zenkoji Temple was open to anyone, thus attracting numerous pilgrims and worshipers. In the latter half of the Edo period, as the living standard of ordinary people rose, visiting Zenkoji temple became even more popular, similar to visiting Ise Shrine and climbing Mt. Fuji.

On a pilgrimage to Dewa Sanzan, three sacred mountains in Yamagata prefecture. (photo: City of Shinjo, Yamagata Prefecture)

Of course, since there were no railroads or cars in the Edo Period, and horses were used exclusively for carrying luggage, people wishing to make the pilgrimage to Zenkoji (or anywhere else) had no choice but to walk - about 40 kilometers per day it is said.

Depending on where a person lived, it could take weeks or months to get to their destination. As with mountain climbing, arriving at the destination is not the end, and walking back home took as long as getting there.

Unlike today, in ancient times making a long journey was for most people a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Such a journey began with both the traveler and those they were leaving behind unsure whether they’d ever see each other again. How that must have felt!

A scene from Kumamoto, southwestern Japan; travelers about to embark on a trip to Zenkoji, on a rented Japan National Railways train car. (photo courtesy of Nippon Travel Agency Co., Ltd.)

As railways began to appear all over the country in the latter half of the Meiji period, Japan’s first travel organization, the Nippon Travel Agency, began renting out use of rails and train cars and conducting tours. The tour to Zenkoji Temple quickly became quite popular.

Considering the clothes these travelers can be seen wearing, it seems there were a lot of wealthy people among them.

There were guidebooks way back in the Edo Period

Before the days of TV and the Internet people may have occasionally heard stories of places far from home. Basically, though, hearing such stories was rare.

Nowadays, travel information is readily available and easily accessible - so much so that people now simply stumble upon information that inspires them to travel. So how did people in the old days get their information?

Perhaps surprisingly, guidebooks in Japan have been around for as far back as the Edo Era.

In the case of the Zenkoji Kaido, there was actually a picture book about famous places along the Zenkoji Kaido titled “Zenkoji-do Meisho-zue”. Written by Toshitada Toyoda and published in 1849, this masterpiece of a guidebook was filled with images of the sights along the road to Zenkoji.

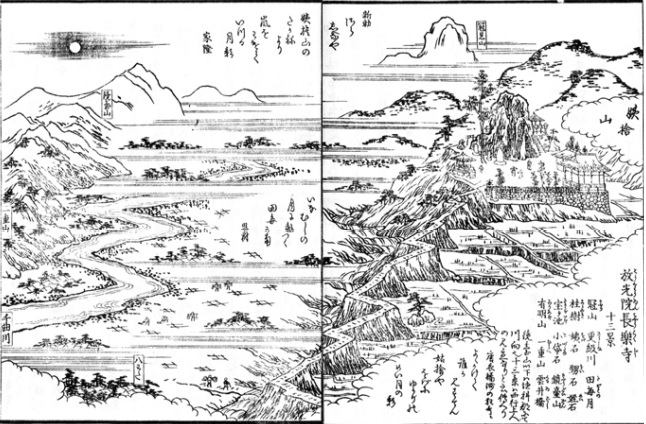

Moon Over the Rice Fields of Obasute, 13 specialties seen from Chorakuji Temple, from the “Zenkoji-do Meisho-zue”.

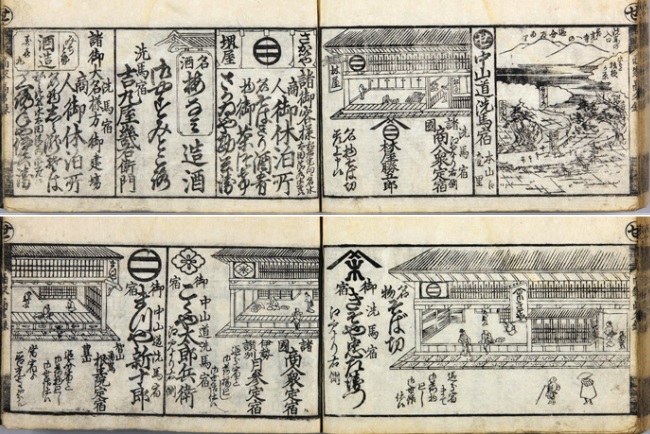

In addition there was another guidebook, the Shokokudochu Shoninkagami, which introduced in detail what kind of restaurants and inns each shukuba post town along Japan’s various kaido offered, along with any local specialties.

Information on Seba-juku, post town at the beginning of the Zenkoji Kaido, from the “Shokokudochu Shoninkagami” (photo courtesy of Shinshu Digital Commons)

It’s interesting to imagine how such a guidebook might have been made. Back in the Edo Era there was not even movable type let alone laptops.

Toshitada Toyoda’s finished works actually consisted of woodblock prints, the product of spending more than ten years traveling Japan’s kaido, collecting information and conducting interviews with the people in the places he went.

After proofreading Toyoda’s writings, calligraphers and painters made a clear copy of each page. Woodcarvers carved the words and images on woodblocks, and “surishi” print masters applied ink to the blocks and pressed sheets of paper over them, producing pages one by one.

For multi-colored ukiyo-e, the famed Edo Era Japanese prints, artisans prepared a separate woodblock for each color, working a single sheet of paper several times to produce one picture. You can see these artists and craftsmen at work in the video below.

Traditional Dress of Pilgrims to Zenkoji

Shigeki Tamura in traditional pilgrim attire. Details in the clothing differ depending on the school.

Temple pilgrims traditionally wear clothes of white, a color symbolizing a pure heart while connoting the power of an amulet. As white clothing is also associated with death, such attire signified the desire of the wearer to be transformed or reborn through their pilgrim journey. So in a way, going on a pilgrimage meant dying - and living anew.

A pilgrim’s white clothes also served to hint at the arduous nature of their trek. Along their way people would sometimes slip or fall, with the stains of their mishaps clearly visible on their clothing. Thus pilgrims who had fallen but continued on their way could be recognized for their efforts by others without saying anything or taking up their time.

The traditional pilgrim’s walking stick, the kongo-zue, is also meant to serve as a sort of “toba”, the long sticks inscribed with Chinese characters and sanskrit seen alongside graves in cemeteries all over Japan. The idea is that if a person perishes in the course of making their pilgrimage their walking stick would become their grave marker.

According to eldery people, temple pilgrims could be seen walking in a long line along the route until sometime after the war. Nowadays it is rare to see people walking the Zenkoji Kaido.

How did people find the money necessary to make such a trip?

A “myogoto” stone tower engraved with the name of a “kou” - a group of local residents who contributed money and other objects for someone preparing for a pilgrimage. (We see a similar concept in a community that collectively funds Buddhist statues, lanterns and stone monuments.) (photo: Shigeki Tamura)

It takes money to travel. A walk through one’s country in the old days was like traveling around the world today - it is not something one can normally do alone.

The solution was establishing the village to collect and save money to be used by members of the community as they took turns visiting sacred sites such as Zenkoji Temple, Ise Shrine, and Mt. Fuji.

The 33 kannon statues carved in stone on the right constitute a replica of a Kannon pilgrimage site in the western part of Japan. Normally, as shown on the left, the principal images for each sacred place would be carved into separate stones. The stone on the right, then, represents an unusual practice. (photos: Shigeki Tamura)

For many, visiting a truly sacred place is a once in a lifetime event, so it’s quite natural to desire an accessible representation of these sacred sites for more frequent moments of worship. In Japan, there are such representations.

For example, in Tokyo there can be found “Fuji-zuka” - mounds and hills of various sizes where one can go in worship of the real Mt. Fuji. In addition, in various places we can see statues of the goddess Kannon. They were made to represent those of the genuine sacred place: the 33 Kannon pilgrimage site in the western part of Japan. In the Shikoku area there is also, among other things, a pilgrimage site with 88 Kannon statues.

As another form of proxy worship, there are places where people can set foot on the soil or sand taken from the sacred site they wish to visit - a simple endeavor that in a spiritual sense is the same as visiting the actual site.

As one comes to understand the beliefs and practices that have for so long been a natural part of the Japanese people’s lives, seeing these various stone monuments along the side of the road creates an interesting feeling - one you can only get when you walk these roads yourself.

What is “Gokaicho”?

I realize I introduced the word “Gokaicho” earlier without offering a full explanation. Now that we’ve arrived at Zenkoji Temple it’s time to take a look at this special event.

photo courtesy of Zenkoji Temple

Zenkoji Nyorai has been hidden from human eyes for a very long time, and now even the monks of Zenkoji Temple are no longer permitted to look upon it. There is, however, a statue called the “Maedachi Honzon” standing in for Zenkoji Temple’s principal object of worship.

Yet even this statue is rarely displayed to the general public. The only opportunity to see, pray to, and worship the Maedachi Honzon is during a once-in-seven-years event called “Gokaicho” when the statue is presented to worshipers from the altar in Zenkoji Temple’s main prayer hall.

Interestingly, while no one is allowed to touch the Maedachi Honzon, people can connect with it in a tangible way. Standing in front of the main hall of Zenkoji is the “Eko-bashira”, a tall, square-shaped pillar. Attached to this pillar is a string that, on the other end, is connected to the “Maedachi Honzon.” By touching the pillar, we are in effect connecting with the Maedachi Honzon.

Like Zenkoji Nyorai, there are many other statues of Buddha that are kept out of sight. There seem to be several reasons for this: to prevent the deterioration of their appearance; to emphasize the value of the main object of worship; to conform in some way to the Shinto practice of enshrining invisible gods; and to prevent secret statues from being seen with an intention that deviates from the original belief. The reasoning behind this last point lies, perhaps, in the fact that some statues are naked, or depict two figures embracing.

Gokaicho lasts from April 3rd to June 29th 2022, the 4th year of Japan’s Reiwa Era. Please see this website for details.

photo courtesy of Zenkoji Temple

One more interesting aspect of Gokaicho is the ritual of having a stamp called the “Go-Inmon-Choudai” pressed against one’s forehead.

The Go-Inmon-Choudai is said to be made of a special kind of gold brought from the legendary underwater castle of Ryugu-jo. It is said that those who have the Go-Inmon Chodai pressed against their foreheads are guaranteed a place in the heavenly Buddhist paradise of the afterlife.

The term Goimon-Choudai also appears in Edo Rakugo, a traditional Japanese form of storytelling, in a story titled “Okechimyaku”.

In the story, a man named Goemon Ishikawa was given a task by Enma, a king who resided in Hell, judging the lives of the people sent before him. Goemon’s task was to return to the realm of humanity to remedy the fact that so few people had been descending to Hell by stealing the Go-Inmon Chodai that allowed people to enter Heaven. Though he completed his mission by stealing the stamp, he pressed it against his own head and in time ended up going to heaven himself.

The allure of the walking pilgrimage. A feeling you can only get by going on your own two feet.

Shigeki Tamura praying on Mt. Kaikoma. (photo: Hiroko Kondo)

No one can make the journey of life for you. And there is no substitute for experience. Zenkoji Temple, a place of profound spirituality, can be reached by train, car, and bus. However, the scenery and the atmosphere of a pilgrimage to Zenkoji can only be felt by walking there.

By praying to the Buddha statues we see, and stopping at the shrines and temples along our way, we can deepen the feeling of our visit to Zenkoji Temple.

In the course of your journey you might get stiff legs, or feel too exhausted to keep walking. But the breezes drifting across your cheeks; the cold spring water bubbling up at your feet; the whispers in your ears of a thousand unseen insects… No doubt you will be moved, and encouraged to keep moving, by the tiny things that too often escape our attention.

Nature. Buddha. The gods all around. It is all much closer out here. To feel it, all you need to do is walk.

Shigeki Tamura, guiding pilgrims along the road to Zenkoji. (photo: Hisahide Seharada)

A walking pilgrimage trip with almost infinite allure. Your opportunity to walk the Zenkoji Kaido, to journey to Zenkoji Temple, just like countless pilgrims in the past, is here.

Next time I will share with you in detail the ins and outs of walking the Zenkoji Kaido, showing you all the highlights along the way. Come on along. Let’s continue our journey.

Author Profile

Shigeki Tamura

・Mountaineering guide

・Practitioner of Shugendo, a form of ascetic mountain worship comprising Shintoism, Buddhism, and traditional folk beliefs.

・First aid extension worker

“Mountain climbing offered direction at a time I was struggling to discover how I wanted to live my life. To pass on the love I found, I became a mountaineering guide, using my knowledge and skills to teach others about the mountains - their history, the beliefs, the ancient roads, and their geography, topography and geology."

Article translated by Welcome-Matsumoto

Original article available here

Page Top

Page Top